Ghana Remains a Bright Spot Amid West Africa's Rising Jurisdictional Risk for Gold Miners

- Ghana remains one of the most stable and investor-friendly jurisdictions for gold mining in West Africa, despite emerging risks.

- Resource nationalism and political instability have escalated in countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, making them significantly riskier.

- Illegal artisanal mining (galamsey) continues to pose challenges in Ghana, but enforcement mechanisms and new regulations are being implemented.

- Newcore Gold’s Enchi project is progressing in Ghana, but investors must assess political risk preparedness and stakeholder engagement.

- ESG compliance, strong permitting frameworks, and legal protections give Ghana an edge, though vigilance against shifting policy remains crucial.

In recent months, geopolitical tensions and policy shifts have thrown the spotlight once again on jurisdictional risk in West Africa, a region renowned for its geological bounty but equally infamous for its political volatility. For investors in junior gold miners such as Perseus Mining and Newcore Gold, which operates in Ghana, these developments raise timely questions: How secure is Ghana as a jurisdiction, and how does it compare to its neighbours?

The answer is layered. Ghana, while not immune to the headwinds reshaping West Africa, still offers relative stability and regulatory clarity. But the region as a whole is undergoing a political shift that could redefine investment frameworks and corporate strategy in Africa for years to come.

The West African Turbulence: Nationalism & Seizures

Several countries in West Africa are tilting toward forms of resource nationalism. In Mali and Burkina Faso, state authorities have already begun to flex their muscles, sometimes unilaterally.

In Burkina Faso, the government recently nationalised five privately held gold assets via its state-owned mining company SOPAMIB. In Mali, Barrick Gold found itself in the headlines after the military used helicopters to forcibly relocate bullion from its Loulo-Gounkoto complex. Meanwhile, Niger, following a military coup, has exited the regional ECOWAS bloc and joined a new security and political alliance with Mali and Burkina Faso, raising red flags about regulatory continuity.

The growing tendency of these regimes to alter contractual terms retroactively or to expropriate assets outright is making investors skittish. Juniors with projects in these countries face the prospect of unstable permitting regimes, rising taxation, and in some cases, full-blown expropriation.

Artisanal Mining: The Double-Edged Sword

Compounding the challenge is the proliferation of illegal artisanal mining, or "galamsey," particularly in Ghana. Although Ghana remains more stable than its Sahelian neighbours, it too is wrestling with the implications of unregulated mining.

Illegal mining not only creates environmental degradation and social tension but also poses threats to licensed operators. Companies must contend with incursions onto their concessions, sometimes resulting in violence or reputational damage. To counter this, the Ghanaian government has introduced new enforcement mechanisms, including the GoldBod (Ghana's new gold marketing board) and a national task force. Some producers have resorted to deploying drones and even enlisting security forces to police their tenements.

While these measures show resolve, they also underscore the growing complexity of operating in what was once considered a gold mining safe haven.

Ghana in Context

Ghana still stands head and shoulders above many of its peers in the region. It has a functioning democracy, a legacy legal framework with British common law underpinnings, and a mining code that has not seen abrupt shifts.

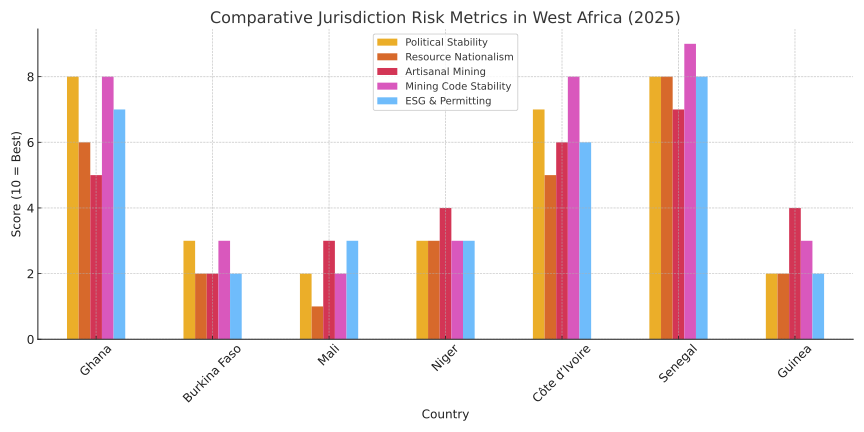

Let us consider the comparative picture:

In this context, Ghana may be considered the best option, particularly for junior and mid-tier developers. While it has not been entirely free of controversy—Gold Fields recently lost its Damang mine lease after the government declined to renew it—it remains among the most favourable jurisdictions in the region for permitting, infrastructure, and legal recourse.

The Ghana Equation

Newcore Gold is currently developing the Enchi Gold Project in southwestern Ghana. The company has recently expanded its drill program to 35,000 metres following strong intercepts, including 4.41 g/t over 24 metres. In February, it raised $15 million in equity financing, providing it with a cash buffer to continue derisking the project.

But investors are right to probe deeper.

What protections does Newcore have in the event of policy changes? How exposed is its concession to artisanal mining? Has the company undertaken political risk insurance? Does it hold clear surface and sub-surface rights, and what is the nature of its engagement with local communities and government agencies?

These are not merely academic questions. They go to the heart of project viability and valuation. Companies such as Newcore must navigate not only geology and capital markets but also an increasingly unpredictable political landscape.

Gold Producer Perseus Mining, on the other hand, has found a formula for operating in Ghana by keeping things local and building genuine relationships with communities around its Edikan gold mine. The company's approach starts with hiring exclusively Ghanaian workers - all 1,100+ employees and contractors are locals who bring years of mining know-how to the operation.

At its core, Perseus wanted to do the right thing and has prioritised weaving themselves into the fabric of local communities. They put $300,000 annually into the Edikan Trust Fund, which isn't just corporate charity - it's managed by a mix of community members, traditional chiefs, and company reps working together on real projects like schools, health clinics, and infrastructure.

This collaborative spirit has helped since Perseus fired up commercial production in 2012, helping them extract over 2 million ounces of gold while maintaining social license to operate and even extending mine life to 2027.

Permitting & Governance: The Ghana Advantage

Ghana’s permitting system remains relatively robust. The country’s Minerals and Mining Act of 2006 has provided a foundation for stability. Fiscal terms are well-understood: a 35% mining tax rate, a 5% royalty, and provisions for repatriation of profits. Ghana also has a proven track record of converting exploration-stage projects into producing mines, with Newmont, Asante Gold, and Gold Fields all operating successfully.

Unlike in Mali or Burkina Faso, mining companies in Ghana still have legal recourse in the event of disputes, and contracts tend to be upheld by the courts. However, the regulatory tide is not static. The rise of the GoldBod and other state-directed initiatives to centralise gold trading and enforce local beneficiation signals a shift toward greater government involvement. The key question is whether this will be executed in a collaborative or coercive fashion.

ESG & Local Dynamics

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues are becoming more central to the investment thesis in Ghana. In part, this is a response to galamsey, which has not only environmental but also political implications.

Companies must now demonstrate that they are contributing to local development, respecting indigenous rights, and avoiding complicity in forced relocations or violence against artisanal miners. This requires active engagement with community leaders, transparent hiring practices, and ongoing dialogue with regulators.

Looking Ahead: Preparedness is Key

For investors, the lesson is clear. Jurisdictional risk in West Africa is not uniform. While Ghana remains relatively secure, the region is shifting, and companies must be prepared.

Key areas to scrutinise include:

- Whether the company holds stabilisation clauses or bilateral investment treaty protections

- The degree of artisanal mining pressure on the asset

- The quality of stakeholder relationships

- The company’s ability to respond to regulatory changes without project derailment

As the geopolitical map of West Africa continues to evolve, the ability to navigate jurisdictional complexity will become as important as grade or recovery rate.

Conclusion: Risk Is Not Binary

Ghana still offers one of the most attractive risk-adjusted environments for gold development in West Africa. But the events in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger serve as a cautionary tale. The rules of the game are changing, and while Ghana remains on the safer side of the spectrum, complacency is not an option.

For companies like Newcore Gold, the challenge is clear: deliver on the technical and economic merits of their projects, while maintaining the social license and political foresight needed to operate in a region where the ground is quite literally shifting beneath their feet.

Analyst's Notes

Subscribe to Our Channel

Stay Informed